Services > Episode 1

Episode 1The Making of the Japanese Translation of Perry’s United States Japan Expedition

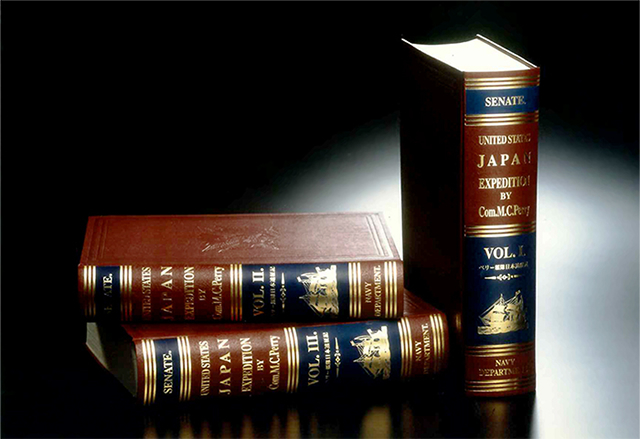

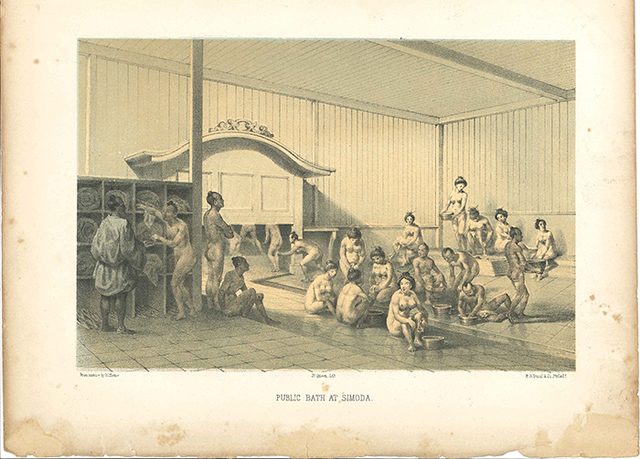

One of Office Miyazaki’s first big projects was producing the Japanese translation of all three volumes of Perry’s United States Japan Expedition. The terribly long title of the first, main volume explains what it contains: “Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Sea and Japan, Performed in the Years 1852, 1853, and 1854, Under the Command of Commodore M.C. Perry, United States Navy, by Order of the Government of the United States, Compiled from the Original Notes and Journals of Commodore Perry and his Officers, at his Request, and Under his Supervision, by Francis L. Hawks, D.D. L.L.D. with Numerous Illustrations.” An important document conveying how Japan was seen from the outside at the time, it is also a fascinating read, and one that changes the way we see the United States and how we evaluate the Tokugawa shogunate.

Published more than 160 years ago, the original work is in A4 format; the first volume is 530 pages, the second 500 pages plus a number of nautical maps, and the third 700 pages—the three volume set makes quite a heavy handful.

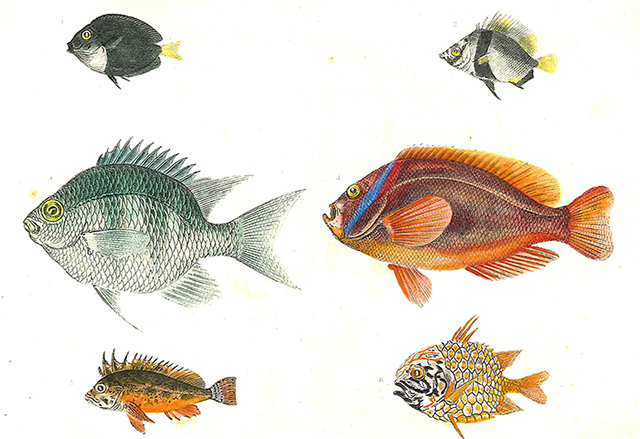

The project came to us unexpectedly and there was a time midway in the project when I thought it would sink the office completely, but we got through it and with the support of the folks at Eikoh Inc. managed to release a Japanese-language replica of these valuable books back in October 1997. The cover of the original edition was discolored after more than 160 years and the embossing squashed, but the lithographs inside were beautiful. The second volume, in particular, which focused on natural history, had colorful illustrations of fish and birds whose ink had not faded at all, and these could be reproduced just as they were. Well received from all quarters—even gaining the recommendation of former US ambassador to Japan Mike Mansfield at time of publication—the project demonstrated what Office Miyazaki was capable of.

The Dawn of DTP

With the emergence of desktop publishing (DTP) software, the 1990s was a time when the Macintosh computer really came into its own. Young staff members at Office Miyazaki had already been using—well, playing with—computers for a long time, and that enabled us to take on the editing and layout of a certain research institute’s English-language journal without hesitation when the request came in and, for the Perry book, to do everything but the actual printing, all the way to the point it was transferred to film, from little Office Miyazaki.

We did the layout of the books so that they were the same size as the original edition and contained roughly the same amount of translated text, spent a bundle on high-end typefaces and a printer that was capable of printing them, and—our inexperience making for a time-consuming process and paper-based copyediting for a great deal of wasted paper—somehow managed to get the final data produced.

Back then you couldn’t just send the PDF data to the printer and get your book made as you can today. First you had to get the data printed on special printing paper, which was then transferred to film. You did this by physically taking the data to a shop that could print on the special printing paper, and then going back to pick it up later. Today there are shops like Vanfu and Kinkos all over the place, but back then there was a shop that specialized in this sort of thing in the entertainment area of Roppongi and we would go back and forth many times a day between Okusawa where our office was then and Roppongi, which, by evening would be filled with tipsy throngs. Making corrections to the text required cutting and pasting the special printing paper for a book that was more that 1,000 pages long. Thinking back on it now makes my head spin. Thanks to the incredible skills of our printer, we managed to complete the set, which weighed in at about 10 kilograms including slipcases.

By the way, back then we did most of our work used Pagemaker software running on a PowerMac.

Volume 2 (Natural History) and Volume 3 (Astronomical Log) Published in Japanese Translation for the First Time

The original edition of United States Japan Expedition was printed in such quantity that it could be considered an American bestseller for its time. Today it is a period piece and a collector’s item. Although the first volume is a fascinating read, the second volume, which we translated into Japanese for the first time, is centered on natural history and contains many beautiful color lithographs. It includes records of a survey of Japanese plants, birds, and fish; those of the flora and fauna of the Bonin Islands (now known as the Ogasawara Islands) are especially precious. The Yamashina Institute for Ornithology reported that publication of this second volume in Japanese led to new discoveries. The sketches of fish would, I am told, have been of greater value had they been produced in finer detail, but the colors were beautiful and the printer told us the inks had not degraded at all.

One disappointment that Commodore Perry himself grumbles about in his introduction to the report on natural history is that the pages devoted to plants are incomplete. Scientists accompanying the expedition such as agriculturist Dr. James Morrow collected samples and produced sketches, discovering a new genus and many new species. The Department of State, however, held onto this information and it was unavailable in time for publication of the second volume, which contains a letter from Morrow to Washington lamenting that later “the French and English, who have each been over the same ground since we explored it, may publish and take all the credit and priority from our government, to which we are entitled, having been the earliest visitors.” The scholarly world seems much the same then and now, doesn’t it? Interestingly, the beginning of the volume contains a letter about the matter from Commodore Perry himself that drips with sarcasm toward the Department of State.

Another appealing aspect of volume two is its nautical maps, said to be the oldest depicting East Asia. The expedition continued its investigation as far north as Hokkaido and the port of Muroran. The port of Muroran is called Endermo Harborde, Hokkaido is called Island of Jesso, and Tokyo Bay is called the Bay of Yedo. At the time, they seem to have dropped lead shot to measure the depth of the sea. In the original edition the maps were bound within volume two, but we had the book disassembled in order to piece together 14 separate maps; for the Japanese edition these were compiled separately so the full set contains three volumes plus the maps. What was really impressive was the skill of the Japanese bookbinders who then put the original edition back together just as it had been before. I can remember the folks at the print shop saying sadly that the craftsmen who had such skills would soon all be gone.

Volume three contains a record of astronomical observations made by expedition member United States Navy Chaplain George Jones. It includes nearly daily observations of the change in zodiacal light (visible to the naked eye, its true nature was not well understood at the time) from 2 April 1853 through 22 April 1855. Jones also observed what was thought to be lunar zodiacal light and compared it with the results of observations made by Cassini in the 1680s. In any case, you have to tip your hat to what must have been a stultifying daily task.

The Challenge of Publishing a Mass-market Version of United States Japan Expedition

The complete three volumes, plus supplemental maps, of the Japanese version of United States Japan Expedition, including an introduction by distinguished historian Yuzo Kato and remarks by a former United States Ambassador to Japan, was released to great fanfare in October 1997. Despite the high cost of the boxed set, I understand hundreds of sets were sold.

An abridged Japanese translation of volume one had been published in a large format edition in 1912. Iwanami Shoten then published this in paperback across four volumes, but with its old kana orthography it was extremely difficult to read. Translating the entire thing from scratch, we aimed to make the text easy to read. Despite putting so much effort into translating the text into Japanese that could be read by high school students—even having veteran editor Yoshio Hirai go through it to ensure readability—the gorgeous replica set of three volumes and maps was so expensive that it did not find its way into high school libraries throughout the country.

Hoping to find a way to make at least the first volume available at a price more within reach, we worked with an amazing publisher called Banraisha to create a mass-market version, even though this meant covering much of the cost out of our pocket. Dr. Kato wrote a new introduction and commentary and veteran editor Kakuko Yanagishima—a sassy Yokohama native—improved the readability of the text even further. Another fun addition to the mass-market version was an essay, written by Hisako Ito, a former researcher at the Yokohama Port Opening Memorial Hall, describing various episodes related to Perry’s expedition, other expeditions to Japan, the warships of the time, and a list of those aboard the “black ships.”

This mass-market edition was re-released in 2014 from Kadokawa Sophia Bunko in an even more affordable format with fewer illustrations. Although it has shrunk with each of its two rebirths, for Office Miyazaki the Japanese translation of United States Japan Expedition is like a treasure box packed with memories. For those of us who have chosen translation as our life’s work, there is a measure of serendipity to the titles we encounter. I am grateful to have been given the chance to learn about the beginnings of the US-Japan relationship—a relationship that has remained indivisible from the end of the shogunate to the present day—as it was seen from the American side.